Things I Wish Someone Told Me About ASP.NET Core WebSockets

There are lots of WebSocket tutorials out there for ASP.NET Core MVC. They all seem great if you are trying to make a demo chat app. Unfortunately, they don’t cover most of the things that are going to trip you up when you go to write a production-ready app. What follows is an assorted list of the things I have learned so far.

By the way, a lot of this list isn’t specific to ASP.NET Core. But since I’ve only implemented WebSockets using ASP.NET Core, that is what I’m writing about.

1. WebSockets Don’t Honor the Same-Origin Policy

Have you ever stopped to wonder why if you visit an evil website that tries to run JavaScript in your browser to connect to your bank, it doesn’t work?

fetch('https://yourbank.example.com/money/transfer', {

method: 'POST',

credentials: 'include',

body: JSON.stringify({

from: '1000000123',

to: '1000000456',

amount: '1 million dollars',

}),

});

This is the browser’s same-origin policy at work protecting you. Other than HTML form submissions, which pre-dates the same-origin policy (and leads to security issues), generally everything in the browser honors the same-origin policy.

Except for WebSockets. WTF.

This leads to a vulnerability known as Cross-Site WebSocket Hijacking (CSWSH). The vulnerability is trivial to exploit by an evil website:

let url = 'wss://vulnerablesite.example.com/websocket';

let ws = new WebSocket(url);

ws.onmessage = console.log.bind(console); // proof-of-concept

An evil website can read every message sent by the vulnerable server to any user who visits the evil website.

Before we talk about the fix, however, we first need to talk about WebSocket authentication.

WebSocket Authentication: Two Schools of Thought

There are two parts of a WebSocket connection: the HTTP handshake and the WebSocket protocol. Unsurprisingly, there are two places we can authenticate the user:

- Auth check in HTTP

- Auth check in WebSocket

Doing the auth check in HTTP means the WebSocket route works like every other route in your app, using cookie auth or whatever you are using. However—without extra work—this can leave you vulnerable to CSWSH.

That makes the alternative look appealing. If you require that clients send their credentials as the first WebSocket message, you avoid any sort of problems with HTTP auth, including CSWSH. From a certain perspective this looks more secure.

Unfortunately, the only way to send credentials over a WebSocket message is to make your credentials readable by JavaScript. This is categorically a bad idea, which has been covered extensively elsewhere.

That means we have to solve the CSWSH problem so we can use HTTP auth.

Preventing CSWSH

The RFC expects your app to consult the Origin header:

The Origin header field is used to protect against unauthorized cross-origin use of a WebSocket server […].

Simply compare the Origin header of the request to a whitelist of allowed origins. Reject any connections from an unknown origin.

One limitation with the suggested approach, however, is that it requires your app to maintain a whitelist of origins, which is inconvenient. As either a replacement mechanism or a supplement, I like to use a variation of the encrypted token pattern. See the demo app I put together for an example of this.

2. WebSocket Frames Aren’t Messages

Most protocols are designed around either a stream-based or a message-based interface:

- Stream-based: think reading bytes from a file (or socket) in a loop until you have consumed the whole stream

- Message-based: think receiving a single, complete JSON (or whatever) blob at a time

WebSockets don’t follow either of these established patterns. Not exactly. With WebSockets each side sends “frames” (why?!?). I think the designers were trying to incorporate the good elements of both streams and messages, but from what I’ve seen it is more like the worst of both worlds.

Most WebSocket tutorials treat ReceiveAsync as if it were a message-based interface. I suppose this works most of the time if you only send small messages.

The good news is that there is a straightforward way to turn ReceiveAsync into a message-based interface:

async Task<(WebSocketReceiveResult, IEnumerable<byte>)> ReceiveFullMessage(

WebSocket socket, CancellationToken cancelToken)

{

WebSocketReceiveResult response;

var message = new List<byte>();

var buffer = new byte[4096];

do

{

response = await socket.ReceiveAsync(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer), cancelToken);

message.AddRange(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer, 0, response.Count));

} while (!response.EndOfMessage);

return (response, message);

}

3. You Need Two Loops For Server Push

If you are writing an echo server demo then you can get away with one loop that calls ReceiveAsync(...) then SendAsync(...), one after the other.

When writing a real-world app, however, you probably need two loops:

- A loop that calls

ReceiveAsync - A loop that calls

SendAsync

Even if the client will never send messages to the server, you still have to call ReceiveAsync. That is, assuming you want to know when the client has disconnected! I found out the hard way that CloseStatus does not get updated unless you keep calling ReceiveAsync.

If you want to push messages from the server to the client, then you will need a second loop running in parallel to send the messages, since chances are the first loop will be unavailable while it is waiting for ReceiveAsync to return.

Here is a sketch of one way to do it:

using (var socket = await context.WebSockets.AcceptWebSocketAsync())

{

// Run a parallel task to wait for events and then send them

var pushTask = Task.Run(() => PushMessages(someMessageSource, socket));

await ReceiveMessages(socket); // Wait for a close message, then return

await pushTask; // Wait for any pending send operations to complete

await socket.CloseAsync(...);

}

Another way you could do it is to push the socket onto a list that would be consumed by a send task that writes messages to all the sockets (or at least the subset of sockets that are supposed to receive a given message). Either way you do it you end up with different loops for sending and receiving.

4. The WebSocket Class Is Not Thread-Safe

You might think that because you are expected to call SendAsync and ReceiveAsync from different threads that the WebSocket class must be thread-safe. And you would be wrong.

Oh, sure, the above scenario is actually supported. It’s just that approximately zero other scenarios are supported. The source code for the class contains this helpful note:

Thread-safety:

- It’s acceptable to call ReceiveAsync and SendAsync in parallel. One of each may run concurrently.

- It’s acceptable to have a pending ReceiveAsync while CloseOutputAsync or CloseAsync is called.

- Attempting to invoke any other operations in parallel may corrupt the instance. Attempting to invoke a send operation while another is in progress or a receive operation while another is in progress will result in an exception.

(Emphasis added.)

If you are not careful, it would be easy for two different simultaneous events in your app to cause SendAsync to be called with different messages at the same time. In case that wasn’t tricky enough, CloseAsync counts as a kind of SendAsync, so you also need to take care with your shutdown flow.

The pattern I used to solve this was to queue all messages for a given client and have a single task be responsible for sending them:

var messages = new ConcurrentQueue();

pushMessageSource.OnMessage += messages.Enqueue;

while (true)

{

if (!messages.TryDequeue(out var message))

{

await Task.Delay(TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(100));

continue;

}

await socket.SendAsync(...);

}

5. Server-side closures: Two Different Kinds

When a client disconnects it can either send a WebSocket close message, or it can let the network connection be terminated abruptly. It makes sense that the server-side logic might distinguish between these two cases. However, it is somewhat inconvenient that ASP.NET Core surfaces these cases in two very different ways.

When the client sends a close message, the server receives it as a message with the type set to Close. On the other hand, a terminated network connection will result in a thrown WebSocketException.

Here is a sketch of how I handled both cases:

try

{

while (true)

{

var response = await socket.ReceiveAsync(...);

if (response.MessageType == WebSocketMessageType.Close)

break;

}

await socket.CloseAsync();

}

catch (WebSocketException ex)

{

switch (ex.WebSocketErrorCode)

{

case WebSocketError.ConnectionClosedPrematurely:

// handle error

default:

// handle error

}

}

Note: my assumption is that either ReceiveAsync or SendAsync could throw a WebSocketException so I make a point to handle both.

6. Client-side closures: You Have To Handle These Too

When all connections between client and server are short-lived, you almost never have to worry about handling dropped connections. Like if a user submits a request, they generally know not to close their laptop lid while it is still submitting (and expect the request to work).

But… if a user simply leaves your site open in a tab, of course at some point they are going to close their laptop lid. Or switch wifi networks. Or maybe the server restarts after a deployment (more on that in the next section).

When writing your client-side code you need to take into account that the WebSocket connection can and will close at the most inconvenient of times.

At the most basic level, the code to handle this is trivial:

const openWebsocket = () => {

let ws = new WebSocket(...);

ws.addEventListener('close', () => setTimeout(openWebsocket, 1000));

// ...the rest of the websocket setup code

};

Simply restart the WebSocket when the close event is raised. (In the real world you would probably want to reconnect using an exponential backoff between attempts, but you get the idea.)

What complicates everything is the window of time when the WebSocket was not connected.

Did the client try to send messages to the server during that time? Maybe you need some sort of queueing mechanism now that holds them until the client reconnects.

Did the server push updates to the client during that time? Maybe the client needs to pull the current state after re-connecting. Or maybe the server could queue messages to the client.

I doubt there is a one-size-fits-all solution to this problem, so you are going to have to figure out what makes the most sense for your app.

7. Clients Can Not Read HTTP Status Codes

Since we are on the topic of client-side logic, it is worth noting that when you new WebSocket(...) in JavaScript and the connection fails for some reason, there is no way (exposed to JavaScript) to see why the connection failed.

When would that matter? Imagine you want your client-side code to distinguish between a general connection failure and an authentication failure—like perhaps the user’s session has expired—and handle each case differently. When you write your server-side logic, it would be natural to reject an authentication failure with a 403, and return some different status code for other cases.

This is all perfectly legal according to the protocol. Except it doesn’t help. When opening a WebSocket connection, JavaScript can not see what HTTP status code the server returned!

The reason why JavaScript can’t do this is rather interesting. Remember how WebSockets don’t honor the same-origin policy? If there was any information available to JavaScript pertaining to a failed connection, a malicious website could use WebSockets to probe networks that the user’s browser is connected to.

The spec is quite explicit about not allowing this:

User agents must not convey any failure information to scripts in a way that would allow a script to distinguish the following situations:

- A server whose host name could not be resolved.

- A server to which packets could not successfully be routed.

- A server that refused the connection on the specified port.

- A server that failed to correctly perform a TLS handshake (e.g., the server certificate can’t be verified).

- A server that did not complete the opening handshake (e.g. because it was not a WebSocket server).

- A WebSocket server that sent a correct opening handshake, but that specified options that caused the client to drop the connection (e.g. the server specified a subprotocol that the client did not offer).

- A WebSocket server that abruptly closed the connection after successfully completing the opening handshake.

The Workaround

It’s easy: instead of returning HTTP status codes return WebSocket status codes.

What the server-side logic looks like in practice:

- Accept the WebSocket connection

- Immediately close the connection, returning a custom close status

The client-side logic can attach to the WebSocket’s close event and look at the ClosEvent.code property to know the reason why the connection was closed/rejected.

What WebSocket status code should I use?

Unlike HTTP status codes, which have well-defined statuses for many common scenarios, like 403 Forbidden etc., the pre-defined WebSocket codes are rather limited.

In practice, your application can define its own codes in the 4000-4999 range, which is reserved for application use.

8. Connections Persist Through Deployments

I assume your production deployment process looks something like this:

- You deploy new code to some servers that are not taking traffic.

- You check to make sure everything looks good. If it does…

- You update your load balancer (or DNS or whatever—doesn’t matter) so that new traffic goes to the servers running the new code.

I want to draw your attention to a key phrase:

update your load balancer […] so that new traffic goes to [the new servers]

You see how this might be a problem?

For short-lived connections everything works out on its own. New connections get routed to the new server. Connections that are in-flight during the switch continue to be processed on the old server, but this is fine because it usually only takes a second or two for existing connections to “drain”, then no connections will be running on the old server.

Long-lived connections are a different story. The load balancer does not know how to migrate existing connections from the old to the new server (and even if it did ASP.NET would not know how to handle it). WebSocket connections that are open during the switchover in the load balancer will continue to run on the old server, until the client disconnects or the application is stopped on the old server.

Assuming you added some sort of client-side reconnect functionality like we talked about in the previous section, then you may not need to do anything extra. Simply let clients reconnect whenever the old server goes offline.

However, there are at least a couple advantages to proactively migrating WebSockets after a deployment:

- All WebSocket connections will be running the latest code server-side.

- You can eliminate the disconnected window by having the client open a new WebSocket connection (to the new server) before closing the existing connection.

One bit of good advice I got was to stagger the time that clients reconnect after a deployment. You don’t want thousands of clients all trying to connect at the same time if you can avoid it.

Finally, if your WebSockets are running as part of a single-page application, you may already have to solve the problem of reloading the new client-side code after a deployment. Depending on how you solve that—perhaps by triggering a full-page refresh—the WebSocket reconnection problem might already be taken care of for you.

9. Connections Persist After User Log Out

This is a variation on the last idea.

When a user’s session expires, any subsequent requests will be rejected until the user logs in again. This works out great for short-lived connections. When a user logs out (or their session expires) they no longer have access to your site.

Surprise, surprise, this is not the case for long-lived connections like WebSockets. Once a user has authenticated to a WebSocket, they will stay connected for as long as their browser stays open and as long as the server has not restarted (like after a deployment). It doesn’t matter if the user’s session was supposed to expire a week ago.

At a minimum, I recommend adding server-side logic to proactively close any WebSocket connection when the associated session expires. A simple way to handle this in .NET is to create a CancellationTokenSource and pass in a TimeSpan representing when the user’s session is supposed to expire, then have the WebSocket handler shut down when the token is canceled. See the demo app I put together for an example of this.

Going further, you could also proactively close the WebSocket when a user actively logs out (prior to the session expiring). This requires additional logic, but shouldn’t be too hard.

10. Some Things Are A Non-Issue

Keepalives

A problem with long-lived connections in general is that network equipment such as routers like to drop connections that appear to have “timed out”.

Fortunately, the WebSocket RFC includes a built-in ping/pong mechanism that can send periodic messages to keep the connection alive. You don’t have to do anything, ASP.NET takes care of it for you:

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

// ...some setup code...

app.UseWebSockets(new WebSocketOptions

{

KeepAliveInterval = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(2),

});

}

You can even omit the option, since the default is to send a keep-alive message every 2 minutes.

Intermediate Proxies

Another network issue you have to consider is that there may be an old HTTP proxy between you and the client that doesn’t understand the WebSocket protocol. Not in your network, of course. I am sure your production network is running the latest-and-greatest. The problem is your client’s network. There always seems to be that one user on a corporate network somewhere that is running locked-down, ancient network hardware.

Do you want to hear one simple trick to never have to worry about outdated network intermediaries again?

OK, here it is: Use TLS!

Make your WebSocket URL start with wss:// and never ws://.

There is basically no excuse for not using TLS in 2018 now that Let’s Encrypt exists.

11. Server-sent Events May Be A Better Fit

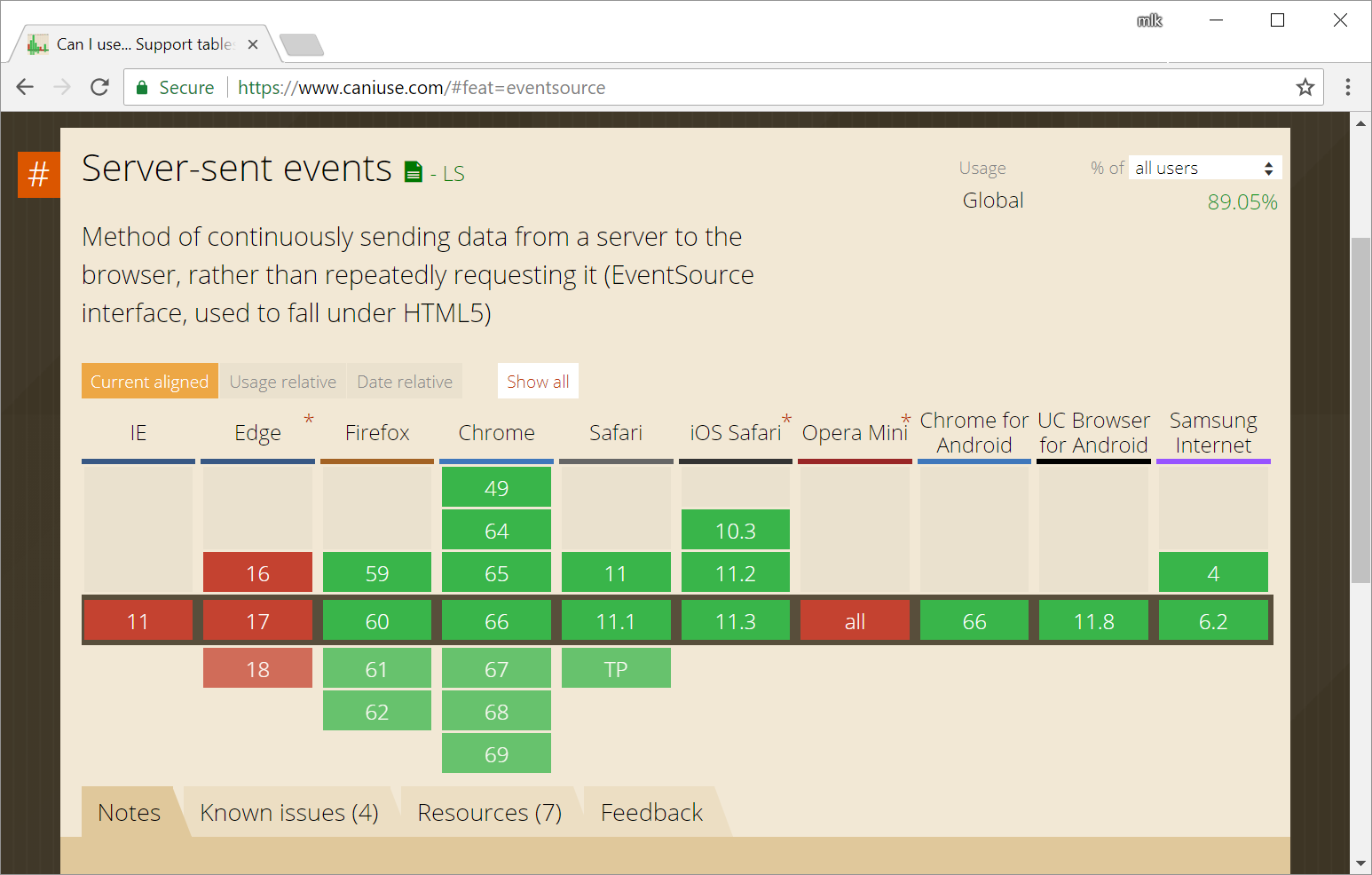

The WebSockets standard is not the only game in town. If what you are trying to do is push messages from the server to the client, take a look at server-sent events. In many ways it seems to be a simpler standard that avoids many of the warts of WebSockets.

There are a couple limitations to be aware of:

- The messages can only be sent from server to client (use normal HTTP requests for the other direction).

- Microsoft has not embraced server-sent events.

Specifically, Microsoft browser support is lacking:

Although it looks like you can polyfill it.

Also, there is no built-in support for server-sent events in ASP.NET Core. However, if you search the web you will find examples implementing it. The examples don’t look too complicated. What is even more promising is that the new version of SignalR is supposed to support server-sent events.

Stuff I Need To Look Into

I am by no means an expert on WebSockets. Take all the above with a grain of salt. Also, I know of at least a couple areas I still need to look into.

Backpressure

Within the context of streams there is a concept called backpressure. The idea is to handle the case where a producer is overwhelming a consumer.

In the case of WebSockets, I am specifically worried about what happens when the server tries to send more messages than the client can handle. There are well established patterns for informing the user when a browser-initiated request is still in progress and is maybe taking a long time. But what about the reverse? Can we detect when the client is falling behind? When we detect it how do we want to handle it?

SignalR

SignalR is Microsoft’s framework for building real-time communication on the web. It is a higher-level abstraction built on top of WebSockets primarily. While SignalR has been around for a long time (it pre-dates WebSockets), the re-write for ASP.NET Core was not available until the recent release of ASP.NET Core 2.1.

I have not evaluated SignalR yet, because when I first implemented WebSocket support a year ago, the Core version of SignalR was still in alpha. Also, I like to implement functionality once without a framework when I can. That way when I do use the framework I know where it is helping me and where it is getting in the way.

I am curious to try SignalR now that it is out to see if it helps with any of the gotchas I outlined in this post.

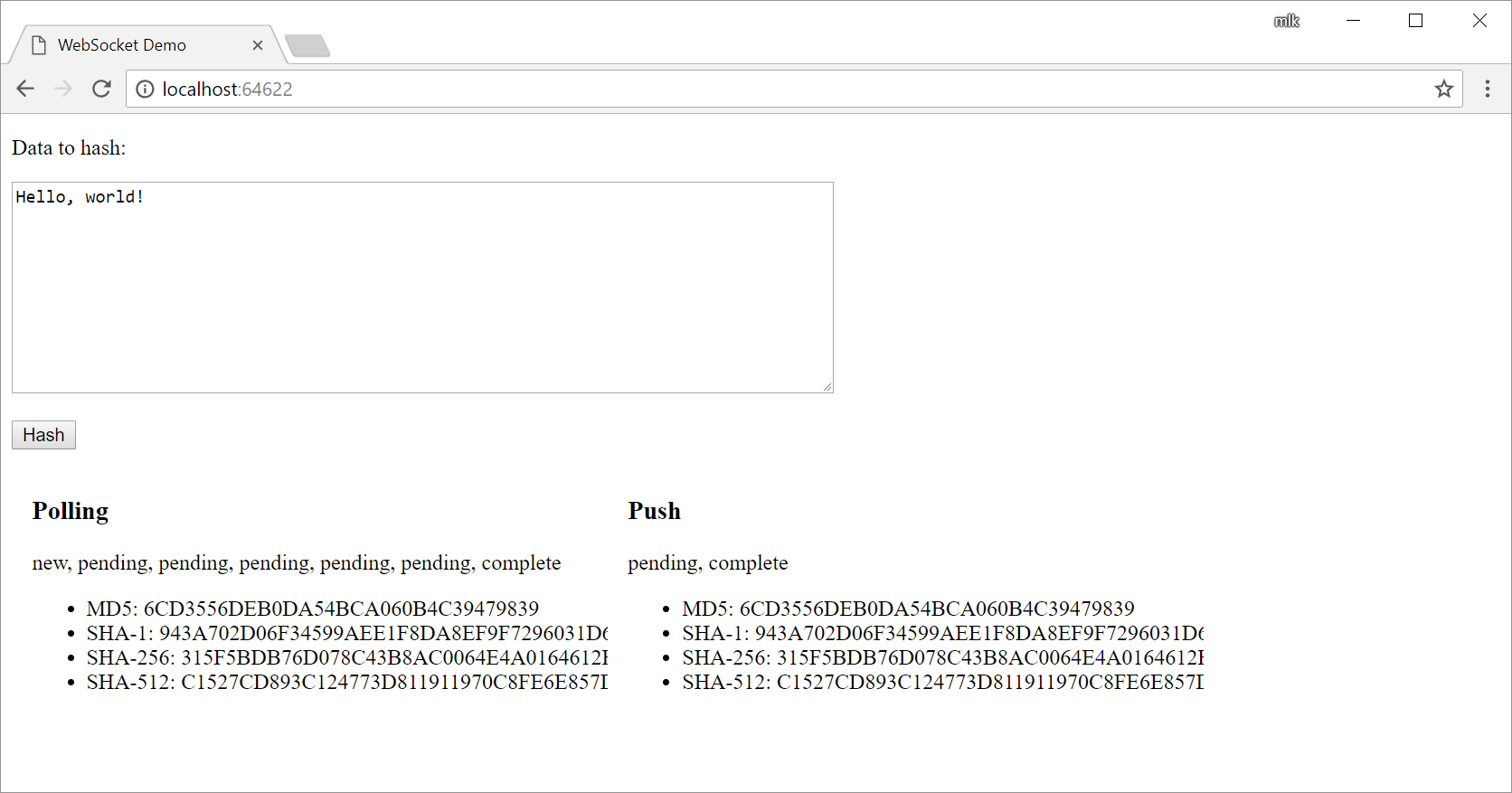

Demo App

I put together a small demo application to play around with some of the concepts in this post. It doesn’t look pretty:

But maybe it will help someone to have running code to play around with.